If you’ve been in the ABA field for a while, you’ve likely noticed a growing interest in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Words like mindfulness, values, and psychological flexibility are appearing in professional conversations, conference talks, and even supervision sessions.

But What Exactly is ACT & How Does It Fit Within ABA?

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is an approach rooted in behavior science, and it helps individuals build psychological flexibility – the ability to act in ways that align with personal values, even when faced with difficult thoughts or emotions.

For BCBAs, ACT offers a framework to support both clients and caregivers in managing internal experiences that influence behavior. Rather than trying to eliminate discomfort or control every thought, ACT teaches people to make space for those experiences while still moving toward what matters most.

Let’s explore how it works and how it can look in practice.

The Foundations: ACT & ABA Work Together

ACT is deeply rooted in behavior analysis. Its foundation lies in Relational Frame Theory (RFT), a behavioral account of language and cognition that explains how we relate words and experiences.

Where traditional ABA often focuses on observable behaviors, ACT helps us understand the private events – thoughts, feelings, sensations – that influence those behaviors.

ACT gives practitioners a more complete toolkit:

- By incorporating behavior change, ACT provides methods for teaching, reinforcing, and shaping behavior.

- ACT adds strategies for helping clients respond more flexibly to their internal worlds.

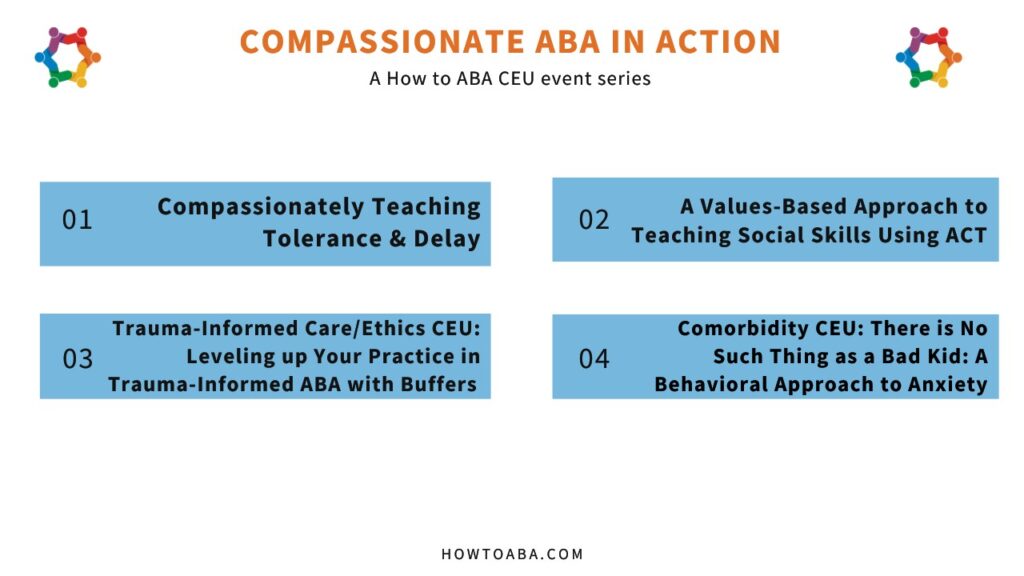

Upgrade your ABA practice with this exclusive 4-CEU bundle designed to help you implement compassionate, trauma-informed strategies while earning CEUs at an incredible value!

The Six Core Processes of ACT

ACT is built around six interrelated processes that cultivate psychological flexibility:

- Acceptance: Making room for uncomfortable thoughts or feelings instead of avoiding them.

- Cognitive Defusion: Learning to see thoughts for what they are – just words or mental events – not literal truths.

- Being Present: Practicing awareness of the current moment with openness and curiosity.

- Self-as-Context: Understanding that we are more than our thoughts or feelings; we can observe them without being defined by them.

- Values: Identifying what truly matters and what gives life meaning.

- Committed Action: Taking steps aligned with values, even when it’s difficult.

When woven into ABA practice, these processes can help clients – and even practitioners – build resilience and self-direction.

A Real-World Example: Using the ACT Matrix with a Student

To see ACT in action, imagine a BCBA named Maria working with Eli, a 12-year-old student diagnosed with autism. Eli is bright and capable, but he struggles with severe test anxiety. Whenever a quiz or writing task comes up, he becomes overwhelmed, refuses to work, and sometimes tears up his paper.

In the past, Maria tried traditional behavior strategies, but Eli’s emotional reactions persisted. She decides to introduce the ACT Matrix as a visual tool to help Eli understand his experience and make more value-driven choices.

Maria draws the matrix, which has two intersecting lines creating four quadrants. The vertical line represents the five senses (experience), and the horizontal line represents behavior (moving toward or away from what matters).

Step 1: Identifying Values (Bottom Right Quadrant)

Maria starts by asking Eli, “Who or what is important to you?” This helps them anchor the conversation in his values. After some discussion about his interests, Eli says, “I want to be good at building robots someday, and I want to have friends who like robots too.”

Maria writes “Being a good learner” and “Being a good friend” in the bottom right quadrant. These are the values – the “toward” moves – that will guide the rest of the exercise.

Step 2: Noticing Internal Barriers (Bottom Left Quadrant)

Next, Maria asks, “When it’s time for a test, what uncomfortable stuff shows up on the inside that can get in the way of being a good learner?”

Eli thinks for a moment and says, “My stomach feels tight, and my brain says, ‘I’m going to fail’ and ‘My friends will think I’m not smart.’”

Maria writes these down in the bottom left quadrant: “tight stomach,” “thought: I’m going to fail,” and “worry: friends will think I’m dumb.” These are the internal experiences – thoughts, feelings, sensations – that show up and pull him “away.”

Step 3: Recognizing “Away” Behaviors (Top Left Quadrant)

Maria then points to the top left quadrant and asks, “When that tight stomach feeling and those worried thoughts show up, what do you do to try to get away from them?”

Eli admits, “I scribble on my paper, put my head down, or rip the test up.”

Maria adds these to the top left quadrant. She explains that these are “away moves” – actions he takes to escape the uncomfortable internal stuff. She also gently points out, “Does ripping up the paper help you move toward being a good learner and making friends?” Eli shakes his head.

Step 4: Brainstorming “Toward” Behaviors (Top Right Quadrant)

Finally, they move to the top right quadrant. Maria asks, “What small action could you take that would move you toward being a good learner, even when your stomach is tight and your brain is noisy?”

This is the “committed action” part. Together, they brainstorm a few workable steps:

Take three deep breaths.

Tell himself, “This is just a worried thought.” Try just the first problem on the page.

Maria writes these in the top right quadrant. These are his “toward moves” – behaviors that align with his values, even if they feel hard in the moment.

By the end of the session, Eli has a visual map of his experience. He can see the connection between his values, his internal “stuff,” and the choices he makes. Maria reinforces his willingness to try these new actions, not because he has to get a perfect score, but because they are steps toward becoming the person he wants to be – a good learner and a good friend. The matrix becomes a tool they can revisit to track his progress and notice his choices.

Upgrade your ABA practice with this exclusive 4-CEU bundle designed to help you implement compassionate, trauma-informed strategies while earning CEUs at an incredible value!

Why ACT Matters in ABA Practice

This kind of flexibility is at the heart of ACT. Instead of trying to eliminate uncomfortable feelings, practitioners teach clients to work with them. For BCBAs, ACT offers plenty of practical benefits:

- With clients: ACT helps individuals tolerate frustration, anxiety, or uncertainty that can interfere with learning new skills.

- With caregivers: ACT strategies can help parents manage guilt, stress, or burnout, leading to better collaboration.

- With practitioners themselves: ACT tools support mindfulness, resilience, and connection to one’s professional values, helping prevent burnout.

By incorporating ACT into behavior programs, BCBAs create opportunities for growth beyond skill acquisition. Clients not only learn what to do but also why they want to do it.

Get Started with ACT

If you’re curious about integrating ACT into your ABA work, here are a few small ways to begin:

- Introduce mindfulness or grounding exercises during sessions.

- Use “values check-ins” when setting goals with clients or caregivers.

- Practice defusion with your own thoughts during challenging sessions.

- Explore ACT-focused CEUs or workshops to build your comfort with the model.

ACT doesn’t replace the foundation of ABA; it enriches it. By helping clients develop psychological flexibility, you’re empowering them to live fuller, more meaningful lives.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy reminds us that behavior change isn’t just about reinforcement schedules or skill acquisition; it’s about helping people build lives they care about.

For Eli, that meant learning to face his anxiety and still reach for his goals. For practitioners, it might mean reconnecting with the “why” behind their work. In the end, that’s what ACT offers: a framework for turning values into action, one meaningful step at a time.